By now it is very likely that you’ve heard the term “digital divide” being thrown around in discussions about equalizing access to computing technologies and the Internet. This term is specially relevant now in the current global context. The COVID-19 pandemic has shone a light on the vital importance of virtual, over-the-internet experiences to ensure continuity in crucial economic and social activities (remote work, e-commerce, banking, food delivery, live-streamed events, etc.)

It is clear that the economic and social effects of the pandemic would have been much, much worse had it occurred at a time in human history without accessible broadband internet access, mobile phones and innovative web technologies. Yet there is still a substantial portion of the human population, about half of the world, without the privilege of having affordable access (or access at all) to the Internet.

Something I’ve noticed is that the digital divide conversation is often discussed as a hardware problem. Experts are either laser-focused on finding affordable ways to build the physical infrastructure needed to establish connectivity, or talking about how Moore’s law and cost-effective manufacturing materials can yield capable and affordable mobile phones for emerging markets. Though the discussion around hardware innovation and access is critical, it eclipses the other half of the problem: software.

Hardware is built to run software. And regardless of how available internet access becomes, if the software is inefficient or unnecessarily bloated, it will offset the capabilities of the hardware.

A useful analogy

Let me put it this way: if you wanted to close the “transportation divide” in a community, what would you do? You would certainly invest in the construction of roads. You would also find ways to get car manufacturers to produce affordable vehicles, and would ramp up the availability and reliability of public transportation.

But what if, after accomplishing all that, you had forgotten to pave the roads and fix all of the potholes? What if all your roads were designed with only one lane and allowed traffic to flow only one way? What if your public transportation options were limited to just the wealthy neighborhoods of your city?

I think you know the point I’m trying to make here: without thoughtful, unbiased attention to design details, the whole system becomes inefficient, messy, exclusive and unsustainable. Infrastructure (the hardware) is only part of the solution. Hardware makes the experience possible. Software makes the experience itself.

Closing the technology-bias divide

I think it is vitally important that we begin to address the role of digital creators (designers, developers, media producers) in ensuring that the platforms, tools, and content we put out into the web do not widen the divide even further.

Just like generational wage gaps that compound over time, the digital divide won’t close equally for all users at the same time. At least not in the beginning. By the time “offline” communities become online, mainstream technology in the developed world (which has been online for almost three decades) will have become increasingly more complex and capable. Soon more and more people will begin to enjoy the blazing-fast speeds of Fiber-optic connections while, at the same time, there are those who will be doing the first Google searches of their lives on a tenuous 3G connection.

I highlight this fact not to guilt those lucky enough to enjoy the conveniences of fast and accessible internet. I simply bring attention to this asymmetry in the evolution of global digitalization as a way to point out that the digital divide will have to be closed within our own perspectives and biases as well.

For example, I’m actually writing this blog post from the rooftop of my apartment building. I’m outdoors. There are no wires or plugs to be seen around me. Instead I’m connected to one of the many “free” Wi-Fi Hotspots made available by my Internet Service Provider across the city. And though the connection is not fast enough to stream a Netflix movie without interruptions, it certainly is adequate enough to do some light browsing and some productive blog writing.

Even though working from my rooftop on a nice sunny day is something I do regularly (and often take for granted!), it is something I try to be aware of. Being aware of your own advantages will help you build more empathetic products and content.

Design for extremes

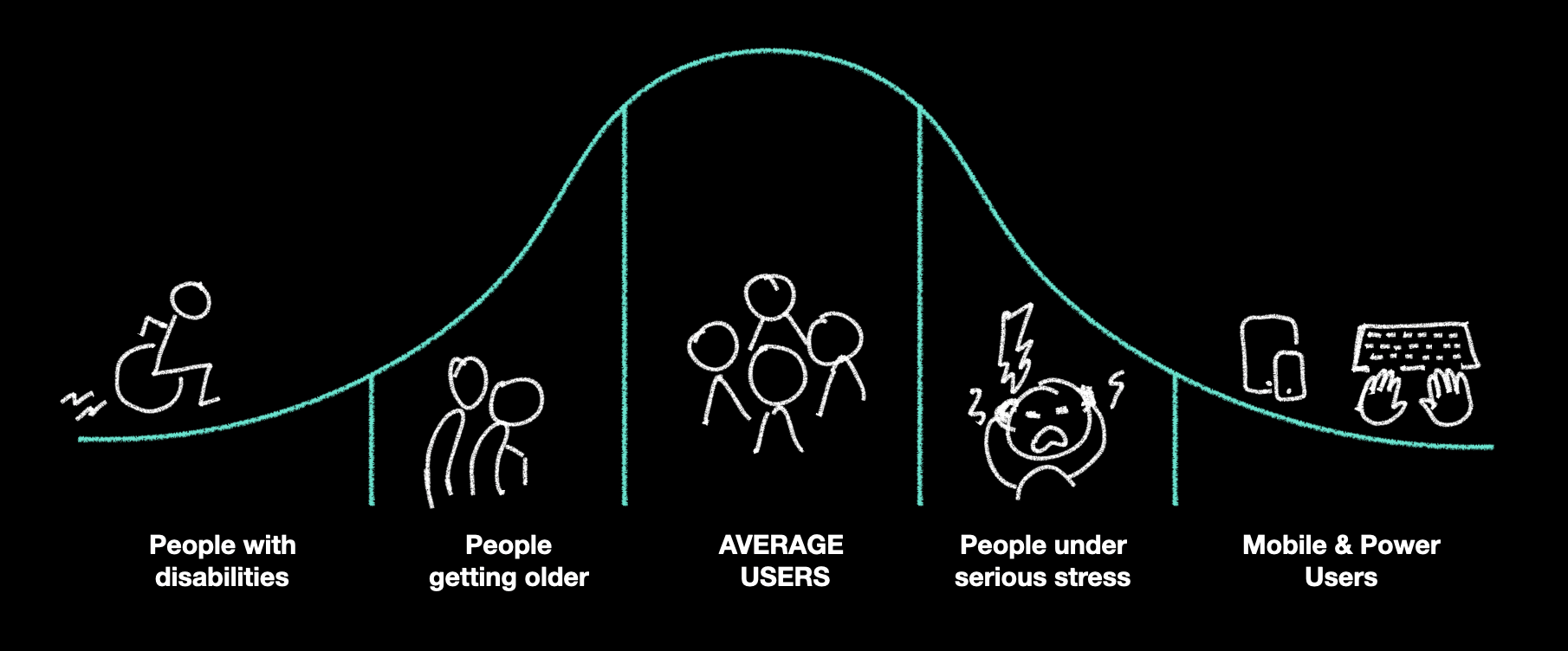

When ideating a solution for a problem, a common human-centered design method is to think about the extremes and mainstreams of your user base. What this method forces you to do is to think about those users who are on the far-ends of the bell-curve in order to empathize with their circumstances and thus ensure your product/experience works for everyone.

Because the progress of capability is fairly linear in technology, it is safe to say that if you build a digital product considering the technological circumstances of people on the left side of the distribution, you’d build an effective and usable experience for the whole user base.

Be conscious of your product’s data footprint

Most of us are used to the Internet as an omnipresent resource. For one, it seems there’s free Wi-fi almost everywhere: in restaurants, cafes, buses, even subway cars! Furthermore most mobile carriers in the U.S. compete with each other by providing unlimited data plans as the default option. No wonder we’re no longer conscious of the real cost of data anymore.

That’s of course not the case for everyone. Consumers in less developed markets have to deal with data caps in the affordable, entry-level plans available. For those users data means money. Even if most websites are in theory free to access, the weight of these (calculated by the aggregate file size of all web page assets: scripts, images, etc.) incur a real cost on the user by chipping away at their mobile plan data allowance.

As you build your next web project, or create your next web content, think about how it will behave at slower speeds, and also about how much the data footprint of your product will impact their ability to affordably keep engaging with it.

In the end, closing the digital divide will require a holistic effort. Infrastructure will have to be built; innovations in hardware will have to deliver better and cheaper personal computing power at scale; and it will also be up to us, those privileged enough to create for a thriving online world, to ensure that when next half of users catches up they will have a great experience doing so.